The Gender Gap

CBC News Online | November 25, 2003

According to Canadian testing on literacy (SAIP), between 1994 and 2002, girls have maintained a significant advantage over boys in reading and writing.

In 1998, at age 13 girls scored on average 15 per cent higher than boys on reading; at age 16 it was 21 per cent higher.

In 2002, at age 16 girls held a 16.5 per cent advantage over boys for writing.

These are consistent with findings from OECD studies on reading.

On average in developed countries, the gender gap is around 15 per cent.

In Canada in 1993, Canadian tests showed girls were underperforming boys by about 9 per cent in math problem solving.

So the gender gap in reading is greater than the gap for math problem solving ever was.

From Dr. Paul Cappon, director general of the Canadian Council of Ministers:

"In summary, the gap which existed one time in mathematics is closed. There

is no gap in science. The gap favouring girls in reading is still wide and the

gap in writing appears to be widening."

From the OECD report Education at a Glance, 2003:

"Already at the 4th grade level, females tend to outperform males in

reading literacy, on average, and at age 15 the gender gap in reading tends to

be large."

University demographics:

In Canada a decade ago, there were about an equal number of males and females. Today, 44 per cent of university students are men and only 40 per cent of graduates are men. That means of university graduates, 60 per cent are women.

This year, 2003, more women then men applied to Canadian medical schools.

INDEPTH: GENDER GAP

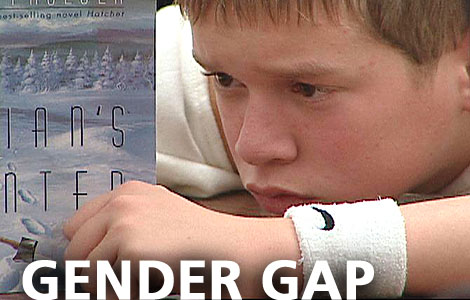

Boy's Own Story

Reporter: Susan Ormiston | Producer: Marijka Hurko | CBC November 25, 2003

A boy's day is like a comic strip, full of conquest and bravado. Every boy is a superhero. But ask most boys and they'll say they'd rather live the adventure than read about it.

This is the story of too many boys who don't read enough, and why passing it off as "boys will be boys" doesn't cut it.

Marc Dowd is 10. His biggest passion is Game Boy. He's spent hours at it and can tell you everything about the characters.

"First was Pokemon," he says. "Then came Digimon. Took out Pokemon. Pokemon was finished. Then Yugio Yugio destroyed Digimon. And Pokemon was finished. Yugio would slaughter them."

He had everyone fooled for years. "First I tried to fake read just with my eyes, moving line to line," he says. "And that seemed to work, so I kept on doing that and then finally my teacher asked me to read and.yow!"

Nothing worked. His parents tried reading to him, they bought books, which gathered dust. Sue and Albert Dowd felt defeated.

"He was seven and I said he's still not reading and then eight and nine and then it was 'he's 10 and something's not right,'" Sue Dowd says.

Albert adds: "[The] worst part, I think I failed. I mean I had done everything I could think of. I liked to read."

But Marc, like most of his chums, would rather kick a ball, watch TV, even sleep.

"I just thought books were useless," he says.

At 10, Marc was at risk of becoming part of a worrisome statistic: there are more boys than girls in trouble with literacy.

"It's mainly girls in the class that enjoy the reading. It's just not a boy habit to read," Marc says.

Marc knew what parents have talked about for years. Many boys lag behind girls in reading and writing for a while. But somehow we assumed developmentally they'd all catch up.

Now it appears that's not so. Educators now say some boys are falling further behind in reading and writing. The gender gap in literacy is significant; it's growing, and some boys may never catch up.

The Canadian Council of Education Ministers tracks these statistics.

Paul Cappon, the director general, says, "We've certainly seen over the last eight or nine years that, whereas girls have closed the gap with boys, because they were behind in math and science, boys have not closed the gap with girls. If anything, they've fallen slightly further behind [in reading] than they were nine to 10 years ago."

It's true of boys here in Canada and in other developed countries: gender influences reading, a revelation for Marc's parents.

"Apparently it's something to do with gender. And I never thought of it in those terms," Albert says.

"I'm hearing it, too," Sue says. "I'm talking to friends and associates and 'Yeah, you know my son's in high school and he's never reading, he's never picked up a book and he's not going to do it.' The girls are reading. The girls are up at night with the flashlight reading under the covers."

Ironically it was the girls we were most worried about 10 years ago. They were falling behind boys in science or math.

Teachers and the women's movement came up with a cottage industry of strategies. Girls-only physics classes, math and science camps, and female role models aimed at closing that gap. That science-math gap was only half as big as the reading gap today with boys.

The efforts with girls worked. Today 30 per cent of engineering students at Canadian universities are young women. Read More ..men then men are applying to medical schools. The demographics are rapidly shifting. Only 10 years ago it was 50-50.

"Now we see that only 44 per cent of university students are men and only 40 per cent of graduates are men, which means 60 per cent of graduates are women. That change in half a generation is an enormous change," Cappon says.

"I can tell you that across the developed world, countries are looking very closely at this issue, trying to figure out strategies and innovative policies and approaches that will work for boys."

You don't have to convince Doug Trimble. He's been a respected principal for 25 years in Hamilton, Ont.

This September, at Cecil B. Stirling elementary school, he launched his own "boys" strategy.

"It's great what we've done for girls, but boys, we're not doing what we need to for boys in school," Trimble says. "[It's a] common fact. People can't argue. Can't debate that one."

In fact, last year at his school boys in Grade 6 scored only half what the girls did in reading. So, this September, Trimble offered kids in Grades 7 and 8, and their parents, a choice. Girls-only, boys-only or co-ed classes. Surprisingly, the single-gender classes were most popular.

"We know that boys lag behind girls at age 13, 14. They're about three to four years behind in language development anyways. So to put those kids in the same classroom where they are language deficient to start with compared to the girlsthat's why they clam up," Trimble says.

The experiment is only a few months old but what do the kids think? We asked Grade 7s in the boys-only class to interview each other.

"I like that there's no girls and you can't be distracted," one boy says. "You get better marks and you can concentrate more"

Would you rather have girls in your class? the boy was asked.

"No," he replied

"Do you still like girls?"

"They're OK."

"What are your favourite subjects in school?" we asked.

"Gym, computers and math," says one.

"Art and gym," answers a second.

"Gym, art and occasionally science," says a third.

Not surprisingly, English never makes the cut. How do you change that?

No one has the magic potion except maybe Harry Potter.

But at least this school is trying a few things. First they gave the boys a male teacher, something rare these days in elementary school. Mr. Thorne's kind of cool.

Dave Thorne tries to engage his boys with a book about them. The novel's called Brian's Winter. It's all about a boy in the wild using just his own wits to survive. Participation in English class is up.

Getting the boys to interact on the stories is a crucial step. "One thing the book hasn't talked about is his water supply with the lake frozen. How is he going to get his water?" Thorne asks. "What would you do?"

"Break the ice, collect it and boil it," one student replies.

Even with a story about bears and caves, it's tough to get a 13-year-old boy's attention. That's a fact. They're just active souls, always moving, which makes school and English literature a challenge.

"[For] girls, spelling, reading, writing is so easy for them. [They] just snap their fingers and read well. The same guy who was willing to take a risk a minute ago won't because there's a girl present," Trimble says.

Trimble's experiment with single-gender classes nudges against two decades of gender equity in education. So has there been any backlash?

"I've had maybe four anonymous phone calls, all from women, suggesting we're trying to put the girls back in the kitchen. 'Barefoot, back in the kitchen,' somebody actually said in one situation," Trimble says. "It's based on not having all the knowledge. Again, the key to our program is providing choice. We're not telling anybody they have to be in a certain classroom."

"He wasn't interested in any of the Treasure Island-type books, you know, or Wind in the Willows I had grown up with and really enjoyed." Albert says.

Albert played his last card: a bribe. What parent hasn't tried that? He made a deal with Marc: every Saturday they'd go first to the bakery for a treat and then to the library. Brownies for books. Marc agreed.

That first Saturday at the public library, they met someone Dad now considers a hero: Joanne Schwartz, the children's librarian.

"Marc told me he picks up a book and he starts to read and the setup of the book with descriptive passages and so on puts him off," Schwartz says. "He just cannot maintain interest through the beginning of the book.

"He was very interested in adventure, that was an important aspect of a book for him. So with that in mind, we sort of wander over to the shelves and there are obvious writers that might fit the bill for him, keeping that in mind. He wants realistic fiction, he wants action-packed drama, so Eric Wilson writes very much with that kind of reader in mind.

"From the first page, something dramatic happens. There's dialogue and off you go. So I chose a couple of books for him to take, just a couple. It worked. It clicked. It's what every librarian wants."

Six weeks later, Marc was reading a book a week, not the classics, but something. Treasure Island didn't cut it.

"I was so hung uphe had to read Treasure Island, the most famous children's book ever written that I read every three or four years over again. That wasn't going to do it. So, you know, I was a Treasure Island failure," Albert says.

"Now every week Marc writes a one-page book review for his dad on the series he loves by author Eric Wilson.

Every Saturday, you'll find father and son at the library, Marc checking out his latest adventure, a warm brownie in his pocket, and Dad poring over, well, you guess.

For Marc there's no more asking it, and it's a huge relief.

"I used to think it's uncool but now I just read books. And on my list in my brain it's a cool thing to do," Marc says.

Did Albert ever worry that the intense focus on reading was going to turn Marc off books forever?

There was a real possibility of that," Albert says. "One of us was going to crack. It was either going to be him or me and I was pretty close to cracking. It got right down to the wire. I think we're all glad Marc's reading."

Just like the storybook promised, for this boy and his dad, a happy ending.

Copyright CBC 2003

INDEPTH: GENDER GAP

Key Resources

CBC News Online | November 25, 2003

EXTERNAL LINKS:

Heather Blair, University of Alberta: more info on her study - http://www.education.ualberta.ca/boysandliteracy

OECD PISA 2000 Knowledge and Skills for Life (PDF - released at the end of 2001) http://www1.oecd.org/publications/e-book/9601141E.PDF

OECD Education at a Glance 2003 - http://www.oecd.org/document/52/0,2340,en_2649_34515_13634484_1_1_1_1,00.html

School Achievement Indicators Program 2002 writing assessment http://www.cmec.ca/saip/scribe3/public/indexe.stm

Canadian Context Document - http://www.cmec.ca/saip/scribe3/public/context-sans.en.pdf