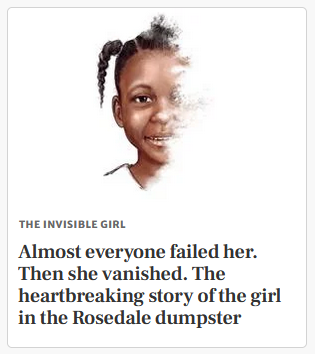

‘Neveah was failed': Rare access reveals haunting details about the life and death of the girl found in a Rosedale dumpster

As part of an ongoing investigation of Neveah - the four-year-old whose remains were found wrapped in blankets in a dumpster in 2022 - the Star recently won access to nearly 1,500 pages of court records.

The Toronto Star, Toronto ON, February 15, 2025

By Wendy Gillis Crime Reporter, and Jennifer Pagliaro Crime Reporter

A rap at the door summoned the woman to the front entrance of a rooming house in east Toronto.

Outside the rundown two-storey home, an empty stroller sat parked by the driveway.

A young boy soon toddled up to the door, followed by two curious school-age girls.

A young boy soon toddled up to the door, followed by two curious school-age girls.

Standing at the stoop, in the heat of a late June afternoon, was a trio of plain clothes officers from the Toronto police homicide squad.

The woman had one question for the detectives at her door.

“How did you find me?”

Only hours before, police had solved one of the most wrenching mysteries in recent Toronto history. More than a year after the decomposed remains of a small girl were found wrapped in blankets in a Rosedale dumpster, investigators had, at last, determined who she was. An anonymous tip, advanced DNA technology and pings off a cellphone tower had brought detectives to this doorstep in June 2023, face-to-face with the girl’s mother.

The children were ushered upstairs. Police needed to deliver the grim news and begin the next phase of their criminal investigation, one focused on a wholly new question about the child they now knew as Neveah.

A composite sketch of Neveah whose body was found in a Rosedale dumpster on May 2, 2022.

Toronto Star Staff Det.

Steve Smith turned on his audio recorder.

“Do you know what happened to her?” he began.

The tragedy that had led police to the mother’s home that day was bigger than the actions of one parent. It was the culmination of a series of failures by a system designed to protect Ontario’s children — a system that did not safeguard a little girl.

As part of its ongoing investigation into the life and death of Neveah — a child with autism spectrum disorder who spent much of her life under Children’s Aid Society supervision — the Star recently gained rare access to nearly 1,500 pages of never-before-seen court records.

These police reports, affidavits from Children’s Aid Society of Toronto (CAST) workers and transcripts from a recent child custody trial paint the most detailed picture yet of how Neveah, a non-verbal child with complex needs, fell through the cracks.

The documents raise new questions about why, just months before Neveah’s death, the child welfare agency advocated for her to be returned to a mother with a lengthy history of substance abuse and neglect — who, even as CAST was vouching for her in court, was the subject of two 911 calls about a child found wandering in just weeks, officers both times finding the mother stressed and overwhelmed.

The records, alongside court testimony from the girl’s mother, foster mother and a lead Toronto police detective, also expose at least five missed opportunities for authorities to realize Neveah was missing — even after police launched a major public appeal for help identifying the girl in the dumpster.

The records, alongside court testimony from the girl’s mother, foster mother and a lead Toronto police detective, also expose at least five missed opportunities for authorities to realize Neveah was missing — even after police launched a major public appeal for help identifying the girl in the dumpster.

At a closed-door hearing, Toronto’s child welfare agency eventually admitted it had been wrong to place Neveah back with her mother, the documents further show.

Last summer, a CAST lawyer implored a judge not to return Neveah’s younger siblings to the mother’s care, saying the agency was “vehemently opposed to that mistake being made a second time.”

“Neveah was failed. The duty owed to her was not upheld,” the lawyer said.

“We should not be finding the dead body of four-year-old children in dumpsters.

”A publication ban prohibits the Star from using Neveah’s full name or from identifying her relatives or foster parents.

Problems right away

Born in 2017 in York Region, Neveah had been taken into child custody at birth after marijuana was found in her system, and placed with a foster parent.

In a generational pattern child welfare experts say is sadly common, Neveah’s mother had herself been placed in CAS care, records show, removed at age 12 from her own mother and permanently placed in the government’s care.

Each of her children were later removed from her custody due to alcohol misuse and neglect, including Neveah, records show.

The mother fought to regain custody of her two youngest kids, Neveah and a younger brother, and eventually won them back under a supervision order, a status that returns kids to a parent while the protection agency keeps watch.

In March 2020, Neveah, nearing age three, and recently diagnosed with autism, and her brother, just shy of age two, were moved from their shared foster home to their mother’s care, contingent on a set of court-ordered conditions.

Problems arose within months. The mother broke a key condition requiring that she reside with a support person who could help care for the children.

She’d moved out of York Region entirely, settling in Toronto. She also did not meet other conditions, including enrolling the kids in daycare five days a week. That was stymied by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A ‘stain’ on Ontario’s child welfare system: Advocates renew calls for accountability in death of Neveah, girl found in Rosedale dumpster

After learning the mother had broken the court’s housing condition, York CAS intervened, drafting another order that kept the kids with her but offered further support. They arranged for in-home care by a private company offering services for autistic children. She was still required to enrol her kids in daycare “as soon as possible” and continue receiving addiction support. No longer having jurisdiction, York CAS also transferred the file to Toronto’s child welfare agency.

By the end of 2020, when many child care centres in Ontario had reopened, the children were still not in daycare.

When it later became apparent the mother had failed to meet other requirements, including taking her children to medical appointments, she claimed in court that she never read any of the custody requirements, court records show.

These missteps do not appear to have had repercussions. In December 2020 — just four months after taking over the file, and at CAST’s first court appearance on Neveah’s case — the agency declared the mother ready for full custody. Child welfare supervision was no longer required, it said.

Neveah’s mother had established a “good working relationship” with her support worker and intended to get a job and improve her family’s circumstances, a court document filed in support of the request states.

She also wanted to pursue counselling to heal from an unspecified “trauma experience. ”

In the court that day, the tone was hopeful.

“Your Honour, having a fresh start with our agency has really been a very positive thing,” a CAST lawyer said.

Neveah and her brother found wandering

Unmentioned at that December 2020 hearing was an incident that happened just eight days earlier. Toronto police had been summoned to a downtown apartment building around 8 p.m. by a call about a lone toddler running around the lobby. It was Neveah.

According to a detailed report written by responding officers, the 911 caller returned Neveah to her apartment, where he found her mother asleep and three other young children unattended (the mother had earlier obtained custody of her two older daughters, then eight and six, on weekends).

One of Neveah’s sisters said her sibling had escaped because the door was unlocked when their mother fell asleep. Groggy, the mother was “uncooperative and defensive” with officers, the record says.

She was unable to provide the full identities of her children and asked the kids to state their own names, the report notes.

“At one point, (the mother) broke down in tears, stating she was under a lot of stress raising her children with little to no assistance,” the record said.

The apartment was in disarray, with toys and various items scattered on the floor, and officers were “unable to identify the reason for (the mother) falling asleep,” the report said.

But the fridge was stocked and the children seemed properly clothed and healthy. They concluded there were no well-being concerns.

Aware of the mother’s child welfare history, CAST was nonetheless advised, the police report said.

At a January 2021 court appearance, CAST continued its effort to end supervision.

The judge, Justice Manjusha Pawagi, pushed back. She noted the mother — unexpectedly absent that morning — hadn’t taken any action. Her kids still weren’t enrolled in daycare, and Neveah wasn’t yet receiving autism support. Pawagi adjourned the case.

That same day the hearing was held, Toronto police were again summoned to where the family was staying, by a “found child” call, this time for Neveah’s two-year-old brother.

Wearing only a diaper, he was found in the lobby alone; the mother arrived moments later to retrieve him.

“Staff advised officers that this was the second incident for (Neveah’s mother) missing a child on the premise,” the report said.

Again, finding the children in good health, officers concluded there were no well-being concerns.

They spoke to the mother about installing an additional lock, purchased by her social worker, that would allow her to wedge open the door for ventilation but prevent her kids from leaving.

The police report again notes the mother “appeared stressed and overwhelmed.

” CAST was notified a second time.

An officer later contacted Neveah’s mother to confirm the lock was installed and noted she seemed to take the matter seriously.

A CAST worker later told police they, too, didn’t have safety concerns and said the woman was “a good mother.” Neither wandering child incident was mentioned at the final March 2021 court appearance where all formal supervision of Neveah and her brother was cut off.

The parties confirmed both kids were, at last, enrolled in daycare and Neveah had an appointment for autism-related services.

There is nothing in the court transcripts about maintaining counselling or addiction services for the mother, a condition of an earlier supervision order from York CAS.

For the first time in Neveah’s short life, she was to be solely in her mother’s care.

“I’m pleased that everything is progressing so well,” Pawagi said.

“I wish you the best of luck with your children. Take care and be safe during the pandemic.”

Neveah vanishes

The plan that placed the kids back in their mother’s care began to unravel within 24 hours.

Neither Neveah nor her brother attended daycare as planned on April 1, 2021 — one day after the court hearing — and Neveah attended just a single day afterward, according to court records. On that occasion, her mother claims, the daycare called her to pick Neveah up early because they weren’t equipped to handle her. Neveah never received the required autism support.

Although the mother agreed to stay in touch with CAST voluntarily, official contact was limited, records show. A society worker made a handful of check-ins that year, including two virtual meetings in May and June 2021. Neveah was visible on the screen during the June 10, 2021 call, a society worker noted.

It would be the last time she was seen alive.

By the time a CAST staffer visited the home a month later, Neveah was not there. When asked about her daughter’s whereabouts, Neveah’s mother said she was at daycare that day. It’s not clear if anyone from the child welfare agency attempted to independently confirm Neveah’s whereabouts.

There’s no record in the documents provided to the Star of further contact with the family before CAST officially closed the file on Nov. 16, 2021.

Two months later, new child protection concerns arose. On Jan. 16, 2022, Toronto police were called by a man who claimed Neveah’s mother was refusing to pay him for moving her furniture. The mover alleged the mother was on drugs and “manhandling” a small child.

When officers arrived, no one answered the door. Concerned about the child’s safety, they entered, finding a unit infested with cockroaches and Neveah’s mother unconscious on a mattress, according to a police report. She “appeared to be under the influence of some sort of substance” and responded to police with a blank stare, the report said.

“Officers attempted to wake the female up by shaking her and yelling for approximately 30 seconds and found no response. Officers had to rub the female’s sternum multiple times to wake her up,” the report said.

Nearby, Neveah’s younger brother was conscious and breathing, but lethargic.

Neveah wasn’t there.

The mother was apprehended under the Mental Health Act, which allows police officers to temporarily take someone into custody when they are a risk to themselves or others. Neveah’s brother, meanwhile, was briefly placed back in CAST’s care.

Alarm bells do not appear to have gone off about Neveah. According to a police occurrence report, while in hospital, the mother asked only where her son was. Court records show that when a CAST worker met with her the next day, she said Neveah was “with her godparents.” She told the society worker that she’d “been ill and under a lot of stress,” but reaffirmed her commitment to placing the children in daycare, according to a CAST worker’s affidavit summarizing the mother’s comments.

Neveah’s brother was returned to his mother a few days later. The records show no effort to confirm Neveah’s whereabouts.

On Jan. 21, 2022, Toronto police were called again, this time for a report that Neveah’s mother was passed out in the back seat of a car, drunk. The caller, an acquaintance of the mother, was concerned about the woman’s children at home, specifying there were four.

Responding officers ran a search, seeing three “CAS Child Need Protection” incidents on file, including one from just days before. A police report notes the mother, who appeared to be under the influence of alcohol, refused to say who had been caring for her children while she was out.

Police records show confusion about how many children were in the mother’s care. The earlier child welfare calls involved four children — Neveah, her younger brother, and the two older sisters on the weekends. Only three were inside.

“The father is taking care of the oldest son,” the police report said, wrongly suggesting there was more than one boy.

Concluding the children were healthy, police said there was no danger. CAST was again notified. A society worker met with Neveah’s mother and her younger brother on Jan. 31, 2022.

Neveah, once more, was not present.

“She reported Neveah was at her godparents’ home again,” an affidavit from a child protection worker said.

It’s unclear whether CAST tried to confirm Neveah’s whereabouts.

Nearly a year after the mother had won back custody of Neveah and her brother, neither child was enrolled in daycare or school.

The mother requested the newly reopened CAST file be closed.

Weeks later, in March 2022, it was — seemingly with no sign of Neveah.

The girl in the Rosedale dumpster

In May 2022, a contractor renovating a home in Toronto’s high-end Rosedale neighbourhood made the tragic discovery of a child’s remains in a dumpster, wrapped in blankets. The finding set off a sprawling police investigation to determine how the child died, and who she was. Forensic tests on her decomposed remains could not pinpoint her cause of death but confirmed she’d been dead for many months or a year.

Investigators scoured reports of missing children and commissioned the girl’s composite sketch, blasting it out to the public. They began canvassing schools and daycares across Ontario — anyone who might have noticed a girl was missing. They approached the province’s child welfare agencies, including CAST.

As the probe continued, new safety concerns were arising, not for Neveah, but for her siblings.

On March 25, 2023, police received separate calls reporting a small child — Neveah’s younger brother — standing in the street in a diaper and no shoes; one caller said he was covered in feces. When authorities arrived, the boy was unharmed and back with his mother, who said he climbed out the window while she was doing dishes.

The police report from the incident erroneously states Neveah — who was by then dead — was present, apparently confusing her with an older sister. The mother gave officers “false information” about her own name and those of the kids, the report said.

CAST was contacted and a newly assigned society worker “made several attempts to meet with (the mother)” including texting her and going to her house, but she would not agree to speak.

“I am OK thank u I’m no need off (sic) service,” the mother texted back on March 27, 2023, court records say.

Three weeks later, a CAST worker emailed police to update them on his failed efforts to speak with Neveah’s mother, including two unannounced visits.

The note refers to just one child.

There is no mention of Neveah.

By early June, CAST learned that the child welfare agency in Peel Region had simultaneously reopened an investigation into two of Neveah’s older sisters — the girls, ages eight and 10, who lived with their maternal grandmother during the week. Their school reported the children were regularly absent on Fridays and Mondays and noticed a decline in the amount and quality of their lunches.

The same day, a CAST worker reached out to Toronto police to ask for help conducting a wellness check on the mother and the boy. The police record from the failed wellness check — no one was home — erroneously stated the mother lived only with the boy and that Neveah was residing with her maternal grandmother in Brampton.

Alarm bells finally seemed to go off when the CAST worker called the grandmother that same day. According to his affidavit, the grandmother said Neveah was with her godparents “but she did not know who they were and had never met them. She had not seen Neveah and did not remember” the last time she saw her, he wrote.

“I became increasingly worried about the children,” the child protection worker wrote.

Neveah, he soon confirmed, was not registered within the Toronto District School Board system. Yet the mother was still receiving funding for Neveah through Ontario Works, the province’s financial assistance program, the society worker learned, meaning Neveah should be living with her.

On June 27, 2023, after several more failed attempts to contact Neveah’s mother, CAST went to court to obtain an apprehension order for the girl and her brother. In their application, the child welfare agency noted Neveah is “unaccounted for” and had not been seen for more than two years.

“I find there is reasonable grounds to believe there is a risk that the children are likely to suffer harm in the care of their mother,” the judge’s ruling said.

Police were already coming to that conclusion themselves.

Forty-eight hours later, detectives confirmed Neveah was the girl in the Rosedale dumpster. After a fruitless year, they’d caught a break using advanced DNA evidence and a tip from the public.

Suddenly, the search was on for Neveah’s mother and the siblings they realized could be in danger.

What happened to Neveah?

As soon as Neveah’s identity was clinched, police looked up her mother’s last known address, but arrived at a darkened, empty home. So they pinged the mother’s cellphone, records show, tracking her to an area in the east end.

Driving around, they spotted the empty stroller outside an east end rooming house. Surmising it could be for Neveah’s brother, they knocked on the door.

She’d moved in the day before.

Smith, a veteran homicide cop who led the effort to identify Neveah, and Det. -Const. Noreen Gordon, an expert in child abuse investigations, told the mother they had information her children shouldn’t hear. Neveah’s eight- and 10-year-old sisters and younger brother went up to the bedroom.

Smith gave the mother Neveah’s official death notification and did not provide details. Her mother began to sob and said little, according to Gordon, who was called to testify at a child protection hearing for Neveah’s two younger brothers last year (Neveah’s mother had a sixth child in January 2024).

“She didn’t have any questions at all about how, where, when,” Gordon told the court.

Smith told the mother he needed to ask some questions. They could go to the police station, but the mother agreed to talk and opted to stay put, so Smith got straight to the point. What happened to Neveah?

“She said Neveah was a lot, that she wasn’t getting a lot of help. She struggled with how to care for her,” Gordon testified.

The mother gave her account. As previously reported by the Star, she claims that sometime in 2021, she and Neveah were at a Tim Hortons when two people, who she knew only as John and Mary, approached her and told her they were godparents who had experience working with autistic children and had facilities for their complex needs. They offered to take Neveah, she said. Struggling to care for her, the mother agreed, and the next day she sent her daughter off with a stroller and clothes.

She watched her walk off with the strangers with only a phone number and a promise to connect.

She never heard from them again, she claimed, despite multiple attempts to call them. She didn’t contact police or CAS to report Neveah missing, she said, because of her negative experience with both institutions.

When the interview was over, Gordon told the mother her remaining kids would have to be taken away.

Toronto police had officially launched a criminal investigation into Neveah’s death and they couldn’t take any chances.

“We don’t know the culpability of anybody in this, including her mother,” Gordon testified.

The mother was upset, Gordon said. Asked if she had anyone she could call, including her own mother, she said no.

The children packed up. Told they were going away from their mom, the 10-year-old took it like a grown-up but quietly cried, Gordon said. The eight-year-old was distraught. The young boy “wanted to be with mom” and didn’t understand what was going on. Gordon watched as the girls stuffed crackers and granola bars into their backpacks and assured them there was going to be food where they were going.

When the kids were put in the car, the younger daughter made a request.

“I want to see my mom and hug her again,” Gordon recalled, saying she let her out of the car for a final goodbye.

“It was heartbreaking,” Gordon told the court. “I did my best to explain what was going on, but I didn’t even have answers for them. ”

A funny girl

The next day, Gordon sat at a child-size table in an interview room in SickKids’ hospital’s Suspected Child Abuse and Neglect unit. Neveah’s 10-year-old sister clutched two stuffed animals she’d brought from home. The eight-year-old bounced a ball against the wall, struggling to sit still.

Interviews with the girls revealed a chaotic life with their mother. Living with their maternal grandmother in Peel Region during the week, on weekends they cycled through their mom’s changing addresses, sometimes living alongside roommates they didn’t know. Some places had bugs and rats, they said.

Yet both girls said they felt safe with their mom and preferred being with her over their “nana,” who one daughter said would discipline them with a slap to the hand or arm, sometimes with a belt. Their mother took them to the mall, or to play outside, and let the elder daughter talk to her friends on a messaging app.

Neither had strong memories of their youngest sister.

When Gordon asked the 10-year-old to name everyone in her family, she listed off her other siblings, grandmother and uncle. Only after Gordon prompted her did she add: “Oh, yeah, Neveah.”

Asked to describe her, both girls said she had autism, meaning she “does stuff that she’s not supposed to and sometimes doesn’t listen,” the eldest said. The younger daughter remarked that Neveah couldn’t speak, but called her sweet.

Neither knew where she had gone.

“When she asked her mom about Neveah, her mom would tell her that she’s with her godparents or foster parents or that she didn’t want to talk about it,” Gordon said of one daughter.

More vivid memories emerged from the eldest sibling, a 13-year-old girl Neveah’s mother lost custody of when she was four, and who lived with her father.

In a November 2023 interview with Gordon, conducted as detectives continued to probe Neveah’s death, the girl said she used to see her mother and siblings every other weekend.

But she’d felt unsafe with her mom’s roommates, who would “smoke and drink, and get drunk in the kitchen.” After she came home with bed bug bites, her dad didn’t want her going back. She hadn’t seen her mother in more than a year.

But she’d spent enough time with Neveah to know she’d been a funny girl — she’d mimic her siblings, to comic effect. When Neveah was upset, she could calm her by turning on the TV. She could also be comforted by a stuffy or a blankie, the girl said.

At the mention of a blanket, Gordon pulled out two pictures: images of two blankets that had wrapped Neveah’s remains, and which police had publicly released photos of, in an effort to identify her. The teen quickly recognized a baby blanket decorated with pastel butterflies.

“It would be the blanket that she’d carry around and stuff with her.”

‘Insight to the mistake made’

Nearly a year to the day that police knocked on her door and removed her children from her care, Neveah’s mother took the witness stand inside family court on Jarvis Street, swearing an oath to tell the truth. She wanted her kids back.

In June 2024, the key players in Neveah’s short life gathered for a high-stakes child protection hearing. The case centred on the custody of Neveah’s two brothers, but it hinged on what happened to the little girl.

The child custody proceeding may be the only trial to examine the circumstances of Neveah’s death, considered suspicious by police.

To this day, there have been no arrests and the case remains unsolved.

Toronto Police Service blanket.

jpg A blanket and that was found with Neveah’s body in a Rosedale construction dumpster on May 2, 2022.

After Neveah’s body was identified, her two older sisters were re-apprehended by Peel CAS (the Star could not verify the outcome of a separate child protection hearing held in their case, and a Peel CAS spokesperson declined to comment, citing confidentiality requirements). CAST, meanwhile, took Neveah’s younger brother back into custody; when the mother gave birth to her sixth child in 2024, he, too, was taken into CAST custody.

Insistent her children were not in danger, Neveah’s mother soon launched a legal battle for her two boys.

At trial, her lawyer defended her as a good mother who had “the utmost love and affection for the children.” Any concerns about substance abuse were at best historical, he said, and she had not been set up for success by CAST after the supervision order ended.

“We do acknowledge that no one is perfect and that the mother did make a mistake in relation to Neveah’s disappearance,” her lawyer Sage Harvey told the court in opening statements.

“What we intend to show, however, is that the mother has insight to the mistake made and that she’s learned from the mistake.”

Harvey declined a request by the Star to speak with him or Neveah’s mother. The Star has been unable to locate Neveah’s mother.

On the stand, much of the mother’s evidence was difficult to parse, her meandering responses prompting reminders from the judge and CAST lawyer to directly answer the question. But her account of how her little girl was, as she claimed, lost, remained unchanged from what she’d told detectives, society workers and lawyers: unable to care for Neveah, she’d given her to strangers she knew only as “John and Mary.”

Months earlier, in pretrial discussions, that account had appeared so far-fetched to Justice Pawagi that she’d asked if CAST was considering a psychiatric evaluation of the mother.

“The explanation, if it is accepted,” the judge said, “is so outside the realm of rational behaviour that I am wondering if the Society (is) seeking an assessment, in terms of cognitive function.”

No assessment was consented to or ordered.

Skeptical, too, police nonetheless looked into the account. Court records reveal that a Toronto detective interviewed the man identified only as “John” and was “satisfied (he) had nothing to do with” Neveah.

“There is no known Mary at this time,” the records said.

Still, the mother insisted her version of events was true.

“I trusted these people. My kids mean everything to me. I would never ever hurt them. I just wasn’t thinking,” she told a society worker, court records show.

The mother said she never reported her daughter missing or sought help due to her own negative experience being separated from her own mother at age 12 and placed in long-term society care.

She feared her other children would again be taken away.

“As a racialized Black woman with a history of Children’s Aid Society involvement, I was terrified that contacting police would have not helped and would have only led to all my children being taken from me,” she wrote in an affidavit.

Asked by her lawyer if she believed it was a mistake to give her daughter away to strangers, Neveah’s mother agreed it was.

“Just because of how everything turned out, where I did not hear from her again. That is one thing I will never — and will always bother me for the rest of my life,” she testified.

She added that she’s working harder to parent her autistic son, though it was easier because, unlike Neveah, he can speak.

She had shared similar sentiments with CAST social workers, who told the court that during supervised visits with the boys she’d been attentive and physically affectionate, often saying “I love you” and “I miss you.”

But she still tried to justify giving away Neveah, who she said was violent toward her younger brother, including pulling his hair and hurling him onto a bed; one worker testified that it made her doubt if the mother understood what she did to Neveah was wrong. The mother blamed her older son’s behavioural problems on her dead daughter, another CAST worker said.

Pressed, during a tense cross-examination by a CAST lawyer, to share something positive about her deceased daughter, the mother said Neveah had had “smiling moments,” but said she struggled to connect with her because she was non-verbal.

And unlike her son, Neveah was taken from her at birth, meaning they didn’t share the same bond.

“I felt that she was confused, due to the fact that she was taken from the hospital (at birth), of who her actual mother was,” she said.

CAST lawyer Chithika Withanage implored the judge to place the boys in permanent care to allow adoption, calling what happened to Neveah “an absolutely horrific tale of abysmal parenting.

” Yet Neveah’s mother didn’t appear to grasp the gravity of what she’d done, she said.

“She keeps calling it a mistake,” Withanage said.

“This is well beyond the scope of a mistake. ”

What had been a mistake, the lawyer conceded, was returning Neveah to her mother’s care. Hindsight is 20/20, she said, “and that’s not a decision that we made in March 2021 that I can defend today.”

Withanage also bemoaned the mystery that surrounds the child’s death, saying she needed to talk about Neveah because “someone has to.”

“This might (be) the last time any attention of this kind is given to this little girl. We don’t know if there will ever be justice for Neveah.

”In July 2024, Justice Wiriranai Kapurura ordered the boys be removed from their mother’s custody permanently. Given the “unacceptably high” risk of returning the children to the mother, it was the only viable plan, the judge said, finding “no child can safely be put in her care. ”

After the Star sent detailed questions for this story, CAST declined to comment on Neveah’s case, citing confidentiality laws. In a statement, the society said it takes seriously the responsibility “to ensure the safety and well-being of children, youth, their caregivers, and broader support networks,” and is accountable to oversight bodies including the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services (MCCSS) and Ontario’s Ombudsman.

‘She was loved’

No funeral was ever held for Neveah, who received a municipal burial in November 2023. But when she was called to testify at the family court hearing, the woman who’d spent the most time with Neveah delivered a kind of eulogy, colouring in the vast gaps of knowledge about the child with vibrant memories.Neveah had arrived at the foster mother’s home at just five days old — “a beautiful baby,” with lovely skin, a healthy appetite and a desire to be cuddled, the woman recalled.

It was the start of a bond. For the next two years, nine months, and 22 days, the foster parents looked after Neveah’s every need. When the couple began noticing delays in her speech and social skills when she was around 18 months old, they took her to doctor’s visits and specialists. Her speech stunted, they learned to read her cues for needs like food, water and sleep.

They found ways to connect.

Her foster father bought Neveah toys and books with texture to engage her in play.

She loved to go to the park, the grocery store or the mall. To be held, hugged and cuddled.

“She was very close to my husband. He would take her for walks in the neighbourhood in her stroller... She had a very safe, loving environment — and because of that, Neveah was not aggressive. She didn’t cry a lot except when she wanted something,” the foster mother said.

Neveah needed constant attention, however. She lacked a sense of danger, the foster mother said — you had to hold her hand while you walked down the street, for instance, or she would dart across. The toddler needed to be watched 24/7, but they were happy to do it.

“It was not challenging for me and my husband,” she said, “because this is the baby we had from five days old, so she became part of our family.”

“She was loved,” the woman said.

Even though she couldn’t speak, the foster family knew the little girl loved them back.

“How did Neveah show affection?” the lawyer for CAST asked the foster mother.

“She would touch your face,” she replied. “She did this from (when) she was a baby.”

In early 2020, when York CAS began transitioning Neveah and her brother back into their mother’s care, the foster parents worked to support her, dropping off children’s beds, a chest of drawers, a toaster oven and groceries.

Neveah approved.

The plan was to keep in touch through regular visits, the foster mother said.

But the COVID-19 pandemic restricted access. Contact was sparse throughout 2020, then fell off in late 2021, when the phone number for the mother stopped working, the foster mother said.

Months later, she got a call from a fellow foster mother, who was sending along a drawing.

It was a composite sketch Toronto police released in their effort to identify the remains of the child found in a dumpster — an artist’s depiction of a young girl with a dark complexion, a trio of braided ponytails and a baby-toothed smile.

“Are you sitting?” the woman had asked.

The foster mother recognized the face the instant she saw it. There, uncannily rendered, was Neveah.

She hung up and called York CAS — “Is this the baby I received?” she asked.

“Is this Neveah?” A supervisor confirmed her dreadful realization.

“It was devastating. My husband took it very badly because he was very attached. And myself, it was as if you lost a child and in a very gruesome circumstance,” she said.

“I don’t think we have recovered from the tragedy of Neveah’s passing.”

Wendy Gillis is a Toronto-based reporter covering crime and policing for the Star.

Reach her by email at wgillis@thestar.ca or follow her on Twitter: @wendygillis.

Jennifer Pagliaro is a Toronto-based crime reporter for the Star. Follow her on Twitter: @jpags.